Software startups are unique in that they have high profit margins (except for LLMs since those have COGS) and can scale quickly. Those margins have never been seen before and make them very attractive, creating a new financier called Venture Capitalists.

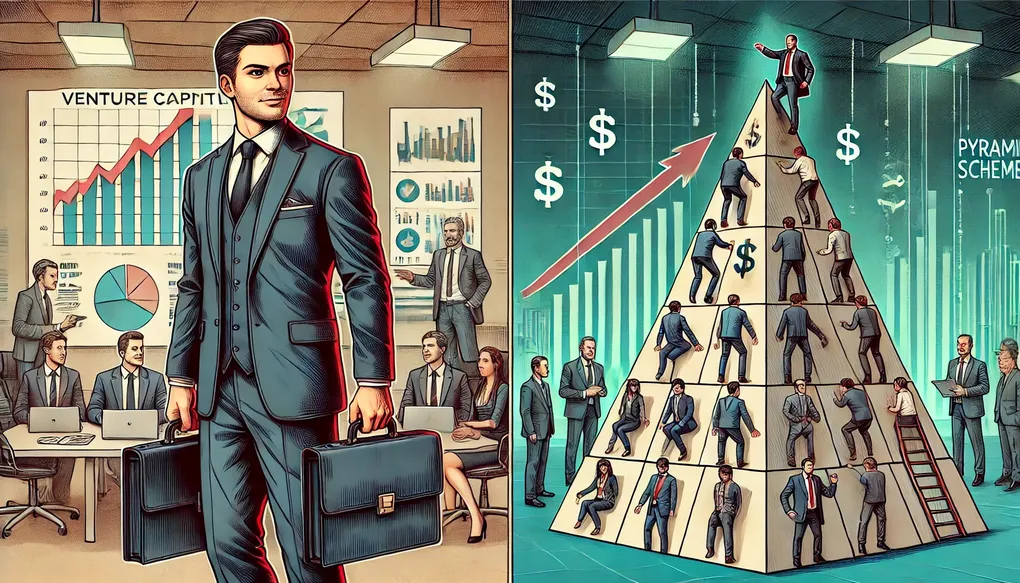

The traditional Venture Capital hypothesis is that most of one’s investments will fail, but the few that succeed will make up for the losses with one being a banger. This only applies to the very top VCs. The rest of the pyramid is a bunch of scalpers of profits.

The Pyramid Scheme

From the perspective of the founder, they’re trying to build a visionary company that revolutionizes an industry — never really the world as portrayed in movies or folklore. Startups follow the principle of using investment dollars to grow the company and eventually sell it to a larger company or go public. Being acquired or going public doesn’t mean they are profitable; in fact, they are rarely except for highly niche companies in difficult-to-differentiate markets (e.g. HR and Payroll, CRMs, etc.). A company that’s never profitable and never believed to be profitable from the CEO’s perspective is a red flag from capitalists’ perspectives.

If startups aren’t profitable, then how do founders make money? During overvalued rounds, founders can sell their shares to new investors in private secondary markets. This is how founders can get paid a ton before an exit, and many don’t exit. Thus, founders can be grifters by building a company that can’t exist by itself. So founders sell their shares and lead shareholders, employees, and their company — their “baby” — to die in a slow manner.

First, founders will need early stage investors; when ideas aren’t entirely proven, early stage VCs with high risk tolerance are required. Founders will get a lead investor who will seek co-investors to fill the round. Getting co-investors reduces the risk for the lead investor.

Secondly, after a startup gets to around Series B, growth-stage investors will buy out more of the company.

Finally — again the company isn’t profitable — the company goes public or is acquired. If the company goes public/IPO, the company will most likely crash. A lot of startups have grand engineered visions but are mostly sales teams propping up numbers and not re-investing in the engineering of the company. Going public allows the growth stage investor to exit. For both acquired or public companies, the last step is for the company to crash or be spun down.

Let’s think about the steps:

- Founders form a company and receive 100% of its shares

- Early stage investors buy 20% of the company using their investors’ money

- Growth stage investors buy 40% of the company using their investors’ money. Early stage investors and founders sell some of their shares and profit.

- The company goes public or is acquired. Growth stage investors and founders sell their shares and profit to public investors, the final victim. If IPO, the company will most likely crash after being unable to shore up its balance sheet.

As a note, there are many strategies. Some founders may never sell secondaries if they have high confidence. This isn’t likely, even for very confident founders, but it grants them more control over the company. A lot of the time, founders will sell secondaries because they see an exit being too far in the future or impossible.

The True Victim

So where did the money come from originally? Institutional investors who have too much money like pension funds, school funds, and family funds. Instead of putting money into truly inventive people and companies, it’s instead put into a pyramid scheme.

Everyone in a pyramid scheme profits but is also a victim. When someone buys in, they’re trapped into waiting to sell to the next victim. But the retail investors, the last in the chain, arguably might not be victims as some profit and some lose. No, the real victims are those putting money into the original funds funneling money into the scheme: those are teachers, retirees, entire nations.

Venture capitalists have high management and carry fees. VCs, even if they completely fail, make money by taking 2% management fees from their funds’ total value and 20% of the profits. This is why VCs are incentivized to raise more within a year from starting, even if they haven’t seen any profits. VCs are incentivized to raise big, but also to not make profits.

The real victims are the pension funders who put money into funds that are supposed to hedge against inflation and financial crises.

How Early-Stage Venture Capital Actually Works

The true story is that most venture capitalists network into the best deals as co-investors and aren’t interested in interviewing and investing in the best founders. Early stage venture capitalists don’t look for bangers. They look for companies that might will end up at Series A so that they can raise their next round, getting a larger pool of money to scalp management fees.

They’re not incentivized to find highly profitable companies; any company works as many of their investments, counter to the original hypothesis, will reach the next round. The lost money from the failed investments is made up by the few, per the hypothesis, but LPs will never see the profits for 10 years. Meanwhile, funds are raised every few years. A VC could be a complete failure, but later investors won’t know until the first fund fails after a decade. The only proof that a VC is winning is false proof that companies that grow to Series B are successful, when in reality, they can’t actually sell their shares.

The entire chain from startups to VCs to LPs is a pyramid scheme

Is there any good startups? I think most startups are good companies that identify problems and solve them; that’s a company after all. These companies all make revenue, it’s just that these aren’t capitalist companies. They’re just a large scheme to profit off the next victim.